Transformational Gardening

May 2011 Foraging Experiences

(Back to:

April 2011 Foraging Experiences)

(Forward to:

June 2011 Foraging Experiences)

May 1, 2011

My first violet posted to this site! Notice how the flowers are bilaterally symetrical.

That means that if you drew a line down the center, the left and right sides would

be the same. This is similar to the human body (the left and right sides are the same).

My first violet posted to this site! Notice how the flowers are bilaterally symetrical.

That means that if you drew a line down the center, the left and right sides would

be the same. This is similar to the human body (the left and right sides are the same).

There are a number of white flower violets in New Hampshire, but this one was easy to

identify because it is the only one with white flowers and a distinct yellow lower

lip. In some cases, the upper petals are tipped with purple. A single flower grows

on a stem originating from the leaf axil. The flower towers well above the leaves.

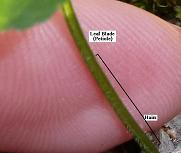

The basal leaves are round to spatulate. The middle and upper leaves tend to be

elliptical with coarsely-rounded teeth. The leaf veins on the underside of the leaf

are hairy.

The basal leaves are round to spatulate. The middle and upper leaves tend to be

elliptical with coarsely-rounded teeth. The leaf veins on the underside of the leaf

are hairy.

I had thought this was Ostrich Fern (Matteuccia struthiopteris) as

almost every foraging guide says to look for a deep groove, brown papery

sheath falling off the fiddlehead and no hairs. Thank you to Frank and to Arthur

for pointing out that this is Intermediate Woodfern. Arthur told me:

I had thought this was Ostrich Fern (Matteuccia struthiopteris) as

almost every foraging guide says to look for a deep groove, brown papery

sheath falling off the fiddlehead and no hairs. Thank you to Frank and to Arthur

for pointing out that this is Intermediate Woodfern. Arthur told me:

“Your plant is a species of Dryopteris (wood fern). Specifically it is Dryopteris intermedia

(evergreen wood fern). Notice that the papery scales on the petiole and leaf blade are very

abundant (not so in Matteuccia). Notice also they are attached to the petiole and will

persist on the plant (not so in Matteuccia, they fall off as the leaf expands). Also notice

all of the remnant leaves from last year lying on the ground pointing away from the fiddleheads

in the center. Those leaves are very different from Matteuccia (too divided and not tapering

to the base).”

May 6, 2011

For me, differentiating between species of violet can be very easy in some cases and

very difficult in other cases. If I had to rely on descriptions in a typical field

guide, I would have no chance, especially in this case. What I think is far better

are step-by-step “Identification Keys”. The one I found the most useful

for Violets in my area is the

New Brunswick Botany Club Violet Indentification Key (also found

in PDF format here).

A couple of other useful keys were the

Northern Ontario Plant Database Violet Key (scroll down to see Key) and the

American Violet Society Dichotomous Key (Eastern U.S.).

For me, differentiating between species of violet can be very easy in some cases and

very difficult in other cases. If I had to rely on descriptions in a typical field

guide, I would have no chance, especially in this case. What I think is far better

are step-by-step “Identification Keys”. The one I found the most useful

for Violets in my area is the

New Brunswick Botany Club Violet Indentification Key (also found

in PDF format here).

A couple of other useful keys were the

Northern Ontario Plant Database Violet Key (scroll down to see Key) and the

American Violet Society Dichotomous Key (Eastern U.S.).

This case was particularly difficult because many botanists and guides

no longer recognize Northern Woodland Violet (Viola septentrionalis) as a

separate species, but now categorize it as part of Viola sororia. Unfortunately,

the written descriptions of Viola septentrionalis sometimes conflict with

that of Viola sororia.

The second row of pictures show that the plant has no above-ground stem -- leaf stems

and flower stems come right from the level of the ground. This eliminated Viola adunca

and Viola labradorica as possibilities. The second picture in the row shows there

are hairs on the lateral (side) petals of the flower. This eliminated Viola selkirkii

as a possibility. In addition, you can see that the little hairs are not dialated

(swollen) at the apex (tip). This eliminated Viola cucullata and Viola

x bissellii as possibilities.

The second row of pictures show that the plant has no above-ground stem -- leaf stems

and flower stems come right from the level of the ground. This eliminated Viola adunca

and Viola labradorica as possibilities. The second picture in the row shows there

are hairs on the lateral (side) petals of the flower. This eliminated Viola selkirkii

as a possibility. In addition, you can see that the little hairs are not dialated

(swollen) at the apex (tip). This eliminated Viola cucullata and Viola

x bissellii as possibilities.

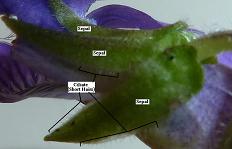

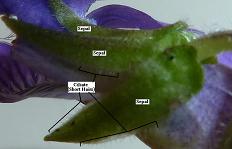

The third row of pictures show that the sepals (the petals that lie under the flower

and are usually green) are ciliate (have short hairs). There are other ways to

differentiate between violets, but I think this is the most efficient process.

This eliminated Viola novae-angliae and Viola nephrophylla as

possibilities.

The third row of pictures show that the sepals (the petals that lie under the flower

and are usually green) are ciliate (have short hairs). There are other ways to

differentiate between violets, but I think this is the most efficient process.

This eliminated Viola novae-angliae and Viola nephrophylla as

possibilities.

The fourth row of pictures shows that the typical leaf is as long or longer than it

is wide. Therefore, I was able to eliminate Viola sagittata var. ovata as a

possibility. According to this Key, the only option left was Viola sororia.

The fourth row of pictures shows that the typical leaf is as long or longer than it

is wide. Therefore, I was able to eliminate Viola sagittata var. ovata as a

possibility. According to this Key, the only option left was Viola sororia.

However, I used the USDA Plant Database search to perform an

Advanced Search to see

what Violets were found in New Hampshire and then proceeded to write down which

were purple or blue violets and which of those were not in the New Brunswick Key

I used. The ones not in the Key were: Viola affinis, Viola rostrata

and Viola septentrionalis. Viola affinis has a hairless or nearly

hairless flower stem. As you can see from pictures below, this flower had a very

hairy flower stem. Viola rostrata has a huge spur (spike) rising up high

from the back of the flower (as can be seen from pictures online). This flower

had no huge spike.

This left either the original Key selection, Viola sororia or

Viola septentrionalis. Several descriptions I ready for Viola

sororia said that the spur flower petal (bottom middle petal) had no

hairs. But as can be seen from the pictures on the fifth row, the bottom

middle flower petal (spur petal) has hairs. Even though Viola septentrionalis

is often categorized under Viola sororia, it has a spur petal with hairs.

This left either the original Key selection, Viola sororia or

Viola septentrionalis. Several descriptions I ready for Viola

sororia said that the spur flower petal (bottom middle petal) had no

hairs. But as can be seen from the pictures on the fifth row, the bottom

middle flower petal (spur petal) has hairs. Even though Viola septentrionalis

is often categorized under Viola sororia, it has a spur petal with hairs.

Viola septentrionalis also fits other descriptions and images that I have

seen including a very hairy stem, some hairs on the leaves, hairs on the leaf

blades and growing in moist open woodlands. Since Viola septentrionalis

is categorized as Viola sororia by most botanists, I decided to do so

as well.

I ate several leaves. They were a touch bitter and it is probably best to

not eat a violet salad without any other ingredients, but they were not bad.

May 7, 2011

Hobblebush (Viburnum lantanoides)

This is a Viburnum with edible berries. The berries are red at first and then

turn black when ripened. I will go back and collect some in the late Summer or Fall.

This is a Viburnum with edible berries. The berries are red at first and then

turn black when ripened. I will go back and collect some in the late Summer or Fall.

These are typical Viburnum flowers with big white 5-petal sterile flowers surrounding

a cluster of little white flowers in the center. The leaves of Viburnum are of

varying shapes, but this is the only Viburnum in New Hampshire that has very

big leaves without deep teeth on the margin. A Couple of useful Viburnum

resources:

Is it a Viburnum? and

Which Viburnum Is It?.

May 8, 2011

Dwarf Nettle has opposite leaves like Stinging Nettle (Urtica dioica), but

its leaves are bigger and have fewer and far deeper teeth. The plant only grows

up to 2 feet tall. It seems to have numerous stinging hairs on the stem and fewer

on the leaves. At this point in the year, the stingers are too flexible to penetrate

the skin.

Dwarf Nettle has opposite leaves like Stinging Nettle (Urtica dioica), but

its leaves are bigger and have fewer and far deeper teeth. The plant only grows

up to 2 feet tall. It seems to have numerous stinging hairs on the stem and fewer

on the leaves. At this point in the year, the stingers are too flexible to penetrate

the skin.

As far as I can tell, Dwarf Nettle is edible just like Stinging Nettle. (See:

“Edible and Useful Plants of Texas and the Southwest: A Practical Guide”

by Delena Tull and

Edible Plants of Florda.) Young leaves can be cooked and eaten. Older leaves

can be used to make a healthy tea to drink or to use for skin treatment (in a

shampoo for example).

As far as I can tell, Dwarf Nettle is edible just like Stinging Nettle. (See:

“Edible and Useful Plants of Texas and the Southwest: A Practical Guide”

by Delena Tull and

Edible Plants of Florda.) Young leaves can be cooked and eaten. Older leaves

can be used to make a healthy tea to drink or to use for skin treatment (in a

shampoo for example).

May 9, 2011

May 10, 2011

I tried raw Trout Lily. It is excellent. Somewhat of a cucumber-like taste. I like it

much better than cooked Trout Lily. Found a huge supply in the woods across the street

from my discovery of Trout Lily in April.

I tried raw Trout Lily. It is excellent. Somewhat of a cucumber-like taste. I like it

much better than cooked Trout Lily. Found a huge supply in the woods across the street

from my discovery of Trout Lily in April.

I have nibbled on young Japanese Barberry leaves a few times.

Wildman Steve Brill has a Wild Food

Application and has proven very useful. He says that the berries are unpleasant and

bitter which I comfirmed last year when I tried making Japanese Barberry jam. He goes

on to say that the young leaves have a pleasant sour taste. Well, I've been trying

them for the last couple of weeks using the youngest possible leaves and I agree that

there is initially a pleasant sour taste, but it is quickly followed by an unpleasant

bitter aftertaste. Maybe I will have to try in mid-April next year.

I have nibbled on young Japanese Barberry leaves a few times.

Wildman Steve Brill has a Wild Food

Application and has proven very useful. He says that the berries are unpleasant and

bitter which I comfirmed last year when I tried making Japanese Barberry jam. He goes

on to say that the young leaves have a pleasant sour taste. Well, I've been trying

them for the last couple of weeks using the youngest possible leaves and I agree that

there is initially a pleasant sour taste, but it is quickly followed by an unpleasant

bitter aftertaste. Maybe I will have to try in mid-April next year.

May 12, 2011

Arrowleaf Violet (Viola sagittata var. ovata)

(Synonym: Viola fimbriatula)

After looking for Canadian Dwarf Cinquefoil all of last year, I found a big patch

50 yards from my front door! Now I can finish differentiating between five of the most

common types of cinquefoil in my area on the

Cinquefoils

Identification page.

After looking for Canadian Dwarf Cinquefoil all of last year, I found a big patch

50 yards from my front door! Now I can finish differentiating between five of the most

common types of cinquefoil in my area on the

Cinquefoils

Identification page.

Differences between Canadian Dwarf Cinquefoil (Potentilla canadensis) and

Common Cinquefoil (Potentilla simplex):

Differences between Canadian Dwarf Cinquefoil (Potentilla canadensis) and

Common Cinquefoil (Potentilla simplex):

- Flower stem arises from the axil of the 2nd leaf for Common Cinquefoil and from the

leaf axil of the first leaf for Canadian Dwarf Cinquefoil.

(Audubon Society field Guide)

- Margin teeth do not go below the top 1/2 of the leaflet for Canadian Dwarf Cinquefoil

and are toothed for approximately 3/4 of their length for Common Cinquefoil.

(Newcomb’s,

Clemants & Gracie)

- Leaflets for Common Cinquefoil are elliptical to somewhat wedge-shaped (obovate)

while the leaflets for Canadian Dwarf Cinquefoil are very obovate, sharting out very thin

at the bottom and relatively very wide at the tip.

(Peterson)

- Hairs on flower stem (peduncle) and leaf stem (petiole) are dense and spreading for

Canadian Dwarf Cinquefoil and are appressed for Common Cinquefoil.

(Weeds of the Northeast,

Clemants & Gracie)

Apparently, Common Cinquefoil can vary anywhere from nearly hairless to appressed hairs.

- Leaflets for Canadian Dwarf Cinquefoil grow up to 1-1/2 inches (4 cm) long and for

Common Cinquefoil the leaflets grow up to 2-1/2 inches (6.5 cm) long.

(Audubon Society field guide)

- The stipules (appendages at the base of the leaf) of the basal leaves are

oblong-lanceolate and flat for Canadian Dwarf Cinquefoil and are linear-lanceolate

and rolled for Common Cinquefoil.

(Weeds of the Northeast)

- The rhizomes (underground stems) for Common Cinquefoil grow up to 3 inches (8 cm)

long while the rhizomes for Canadian Dwarf Cinquefoil only grow up to 3/4 inches (2 cm)

long.

(Weeds of the Northeast)

- Canadian Dwarf Cinquefoil bloom from April until June while Common Cinquefoil

blooms from May until July.

NH Wildflowers Color Thumbnails: Yellow

May 17, 2011

May 20, 2011

Starflower (Trientalis borealis)

May 21, 2011

Very distinctive pair of purple flowers. I saw it last year, but after it was done

flowering, I could not recognize it. Notice that the leaves congregate near the top

as if they are whorled, but in the pictures (2nd row) you can see that they actually

alternate near the top of the stem. The leaves have no teeth (entire) and have a very

slight red tinge near the outer edge.

Very distinctive pair of purple flowers. I saw it last year, but after it was done

flowering, I could not recognize it. Notice that the leaves congregate near the top

as if they are whorled, but in the pictures (2nd row) you can see that they actually

alternate near the top of the stem. The leaves have no teeth (entire) and have a very

slight red tinge near the outer edge.

May 28, 2011

I used the

USDA Plant Database Advanced Search to list every plant in

New Hampshire that is a member of the Pea family (Fabaceae)

and then went through all of them to make sure I had this identification

correct. In addition, I used the Weed

Identification Software to begin the identification process.

I used the

USDA Plant Database Advanced Search to list every plant in

New Hampshire that is a member of the Pea family (Fabaceae)

and then went through all of them to make sure I had this identification

correct. In addition, I used the Weed

Identification Software to begin the identification process.

There is another species of Lupine found in the Northern part of New Hampshire

(Coos County) and in the Southwestern part of New Hampshire (Cheshire County).

It is called Big Leaf Lupine (Lupinus polyphyllus). It

has 11-17 palmately divided leaflets. The leaflets are much longer with a

pointed tip.

There is another species of Lupine found in the Northern part of New Hampshire

(Coos County) and in the Southwestern part of New Hampshire (Cheshire County).

It is called Big Leaf Lupine (Lupinus polyphyllus). It

has 11-17 palmately divided leaflets. The leaflets are much longer with a

pointed tip.

May 30, 2011

In New Hampshire, there are only a small number of Viburnums with lobed leaves:

In New Hampshire, there are only a small number of Viburnums with lobed leaves:

- American Cranberrybush (Viburnum opulus var. americanum)

- European Cranberrybush (Viburnum opulus var. opulus)

- Mapleleaf Viburnum (Viburnum acerifolium)

- Squashberry (Viburnum edule)

One of the most obvious differences is that Mapleleaf Viburnum and Squashberry

do not have the large, showy sterile flowers. They only have the smaller white flowers.

Also, Mapleleaf Viburnum does not have swollen glands on the leaf petioles. The

margins of Squashberry leaves have many teeth compared to the few teeth on the

leaf margins of Cranberrybush.

The Peterson Field Guide for Edible Plants says, ‘A European

ornamental occasionally escaped from cultivation,

V. opulus [Viburnum opulus var. opulus], is

almost a double for Highbush-cranberry, but with bitter fruit.”

For this reason, it is important to tell the two apart.

The Peterson Field Guide for Edible Plants says, ‘A European

ornamental occasionally escaped from cultivation,

V. opulus [Viburnum opulus var. opulus], is

almost a double for Highbush-cranberry, but with bitter fruit.”

For this reason, it is important to tell the two apart.

The following web page shows how to tell the two apart (using

a table and two links for pictures):

http://oregonstate.edu/dept/ldplants/vitr.htm. The American

Cranberrybush has a wide and shallow groove on the leaf petiole,

small glands on the petiole and hairs only the leaf veins of the underside

of the leaf. The European Cranberrybush has a thin groove

on the leaf petiole, larger, disk-shaped glands on the petiole and

hairs on the underside of the leaf in addition to the leaf vein hairs.

The leaves are edible (raw or cooked) when gathered in April or May before the flowering

stem appears. At this time, any slight bitterness can be reduced with cooking. Changes

to cooking water can reduce bitterness if the leaves are picked later in the Spring

after flowering. The rosette of leaves produced in the Fall tends to be mild and

can be collected into the very late Fall.

The leaves are edible (raw or cooked) when gathered in April or May before the flowering

stem appears. At this time, any slight bitterness can be reduced with cooking. Changes

to cooking water can reduce bitterness if the leaves are picked later in the Spring

after flowering. The rosette of leaves produced in the Fall tends to be mild and

can be collected into the very late Fall.

The picture I took were not very clear for showing the alternate leaf arrangement

and the hairs on the stem and leaves. I will go back over the next couple of

weeks and take more pictures which you will be able to find at:

http://www.transformationalgardening.com/forage/plants/hesperis-matronalis-images.html.

My first violet posted to this site! Notice how the flowers are bilaterally symetrical.

That means that if you drew a line down the center, the left and right sides would

be the same. This is similar to the human body (the left and right sides are the same).

My first violet posted to this site! Notice how the flowers are bilaterally symetrical.

That means that if you drew a line down the center, the left and right sides would

be the same. This is similar to the human body (the left and right sides are the same).

The basal leaves are round to spatulate. The middle and upper leaves tend to be

elliptical with coarsely-rounded teeth. The leaf veins on the underside of the leaf

are hairy.

The basal leaves are round to spatulate. The middle and upper leaves tend to be

elliptical with coarsely-rounded teeth. The leaf veins on the underside of the leaf

are hairy.

I had thought this was Ostrich Fern (Matteuccia struthiopteris) as

almost every foraging guide says to look for a deep groove, brown papery

sheath falling off the fiddlehead and no hairs. Thank you to Frank and to Arthur

for pointing out that this is Intermediate Woodfern. Arthur told me:

I had thought this was Ostrich Fern (Matteuccia struthiopteris) as

almost every foraging guide says to look for a deep groove, brown papery

sheath falling off the fiddlehead and no hairs. Thank you to Frank and to Arthur

for pointing out that this is Intermediate Woodfern. Arthur told me:

For me, differentiating between species of violet can be very easy in some cases and

very difficult in other cases. If I had to rely on descriptions in a typical field

guide, I would have no chance, especially in this case. What I think is far better

are step-by-step “Identification Keys”. The one I found the most useful

for Violets in my area is the

New Brunswick Botany Club Violet Indentification Key (also found

in PDF format here).

A couple of other useful keys were the

Northern Ontario Plant Database Violet Key (scroll down to see Key) and the

American Violet Society Dichotomous Key (Eastern U.S.).

For me, differentiating between species of violet can be very easy in some cases and

very difficult in other cases. If I had to rely on descriptions in a typical field

guide, I would have no chance, especially in this case. What I think is far better

are step-by-step “Identification Keys”. The one I found the most useful

for Violets in my area is the

New Brunswick Botany Club Violet Indentification Key (also found

in PDF format here).

A couple of other useful keys were the

Northern Ontario Plant Database Violet Key (scroll down to see Key) and the

American Violet Society Dichotomous Key (Eastern U.S.).

The second row of pictures show that the plant has no above-ground stem -- leaf stems

and flower stems come right from the level of the ground. This eliminated Viola adunca

and Viola labradorica as possibilities. The second picture in the row shows there

are hairs on the lateral (side) petals of the flower. This eliminated Viola selkirkii

as a possibility. In addition, you can see that the little hairs are not dialated

(swollen) at the apex (tip). This eliminated Viola cucullata and Viola

x bissellii as possibilities.

The second row of pictures show that the plant has no above-ground stem -- leaf stems

and flower stems come right from the level of the ground. This eliminated Viola adunca

and Viola labradorica as possibilities. The second picture in the row shows there

are hairs on the lateral (side) petals of the flower. This eliminated Viola selkirkii

as a possibility. In addition, you can see that the little hairs are not dialated

(swollen) at the apex (tip). This eliminated Viola cucullata and Viola

x bissellii as possibilities.

The third row of pictures show that the sepals (the petals that lie under the flower

and are usually green) are ciliate (have short hairs). There are other ways to

differentiate between violets, but I think this is the most efficient process.

This eliminated Viola novae-angliae and Viola nephrophylla as

possibilities.

The third row of pictures show that the sepals (the petals that lie under the flower

and are usually green) are ciliate (have short hairs). There are other ways to

differentiate between violets, but I think this is the most efficient process.

This eliminated Viola novae-angliae and Viola nephrophylla as

possibilities.

The fourth row of pictures shows that the typical leaf is as long or longer than it

is wide. Therefore, I was able to eliminate Viola sagittata var. ovata as a

possibility. According to this Key, the only option left was Viola sororia.

The fourth row of pictures shows that the typical leaf is as long or longer than it

is wide. Therefore, I was able to eliminate Viola sagittata var. ovata as a

possibility. According to this Key, the only option left was Viola sororia.

This left either the original Key selection, Viola sororia or

Viola septentrionalis. Several descriptions I ready for Viola

sororia said that the spur flower petal (bottom middle petal) had no

hairs. But as can be seen from the pictures on the fifth row, the bottom

middle flower petal (spur petal) has hairs. Even though Viola septentrionalis

is often categorized under Viola sororia, it has a spur petal with hairs.

This left either the original Key selection, Viola sororia or

Viola septentrionalis. Several descriptions I ready for Viola

sororia said that the spur flower petal (bottom middle petal) had no

hairs. But as can be seen from the pictures on the fifth row, the bottom

middle flower petal (spur petal) has hairs. Even though Viola septentrionalis

is often categorized under Viola sororia, it has a spur petal with hairs.

This is a Viburnum with edible berries. The berries are red at first and then

turn black when ripened. I will go back and collect some in the late Summer or Fall.

This is a Viburnum with edible berries. The berries are red at first and then

turn black when ripened. I will go back and collect some in the late Summer or Fall.

Dwarf Nettle has opposite leaves like Stinging Nettle (Urtica dioica), but

its leaves are bigger and have fewer and far deeper teeth. The plant only grows

up to 2 feet tall. It seems to have numerous stinging hairs on the stem and fewer

on the leaves. At this point in the year, the stingers are too flexible to penetrate

the skin.

Dwarf Nettle has opposite leaves like Stinging Nettle (Urtica dioica), but

its leaves are bigger and have fewer and far deeper teeth. The plant only grows

up to 2 feet tall. It seems to have numerous stinging hairs on the stem and fewer

on the leaves. At this point in the year, the stingers are too flexible to penetrate

the skin.

As far as I can tell, Dwarf Nettle is edible just like Stinging Nettle. (See:

“Edible and Useful Plants of Texas and the Southwest: A Practical Guide”

by Delena Tull and

Edible Plants of Florda.) Young leaves can be cooked and eaten. Older leaves

can be used to make a healthy tea to drink or to use for skin treatment (in a

shampoo for example).

As far as I can tell, Dwarf Nettle is edible just like Stinging Nettle. (See:

“Edible and Useful Plants of Texas and the Southwest: A Practical Guide”

by Delena Tull and

Edible Plants of Florda.) Young leaves can be cooked and eaten. Older leaves

can be used to make a healthy tea to drink or to use for skin treatment (in a

shampoo for example).

I tried raw Trout Lily. It is excellent. Somewhat of a cucumber-like taste. I like it

much better than cooked Trout Lily. Found a huge supply in the woods across the street

from my discovery of Trout Lily in April.

I tried raw Trout Lily. It is excellent. Somewhat of a cucumber-like taste. I like it

much better than cooked Trout Lily. Found a huge supply in the woods across the street

from my discovery of Trout Lily in April.

I have nibbled on young Japanese Barberry leaves a few times.

Wildman Steve Brill has a Wild Food

Application and has proven very useful. He says that the berries are unpleasant and

bitter which I comfirmed last year when I tried making Japanese Barberry jam. He goes

on to say that the young leaves have a pleasant sour taste. Well, I've been trying

them for the last couple of weeks using the youngest possible leaves and I agree that

there is initially a pleasant sour taste, but it is quickly followed by an unpleasant

bitter aftertaste. Maybe I will have to try in mid-April next year.

I have nibbled on young Japanese Barberry leaves a few times.

Wildman Steve Brill has a Wild Food

Application and has proven very useful. He says that the berries are unpleasant and

bitter which I comfirmed last year when I tried making Japanese Barberry jam. He goes

on to say that the young leaves have a pleasant sour taste. Well, I've been trying

them for the last couple of weeks using the youngest possible leaves and I agree that

there is initially a pleasant sour taste, but it is quickly followed by an unpleasant

bitter aftertaste. Maybe I will have to try in mid-April next year.

After looking for Canadian Dwarf Cinquefoil all of last year, I found a big patch

50 yards from my front door! Now I can finish differentiating between five of the most

common types of cinquefoil in my area on the

Cinquefoils

Identification page.

After looking for Canadian Dwarf Cinquefoil all of last year, I found a big patch

50 yards from my front door! Now I can finish differentiating between five of the most

common types of cinquefoil in my area on the

Cinquefoils

Identification page.

Differences between Canadian Dwarf Cinquefoil (Potentilla canadensis) and

Common Cinquefoil (Potentilla simplex):

Differences between Canadian Dwarf Cinquefoil (Potentilla canadensis) and

Common Cinquefoil (Potentilla simplex):

Very distinctive pair of purple flowers. I saw it last year, but after it was done

flowering, I could not recognize it. Notice that the leaves congregate near the top

as if they are whorled, but in the pictures (2nd row) you can see that they actually

alternate near the top of the stem. The leaves have no teeth (entire) and have a very

slight red tinge near the outer edge.

Very distinctive pair of purple flowers. I saw it last year, but after it was done

flowering, I could not recognize it. Notice that the leaves congregate near the top

as if they are whorled, but in the pictures (2nd row) you can see that they actually

alternate near the top of the stem. The leaves have no teeth (entire) and have a very

slight red tinge near the outer edge.

I used the

USDA Plant Database Advanced Search to list every plant in

New Hampshire that is a member of the Pea family (Fabaceae)

and then went through all of them to make sure I had this identification

correct. In addition, I used the Weed

Identification Software to begin the identification process.

I used the

USDA Plant Database Advanced Search to list every plant in

New Hampshire that is a member of the Pea family (Fabaceae)

and then went through all of them to make sure I had this identification

correct. In addition, I used the Weed

Identification Software to begin the identification process.

There is another species of Lupine found in the Northern part of New Hampshire

(Coos County) and in the Southwestern part of New Hampshire (Cheshire County).

It is called Big Leaf Lupine (Lupinus polyphyllus). It

has 11-17 palmately divided leaflets. The leaflets are much longer with a

pointed tip.

There is another species of Lupine found in the Northern part of New Hampshire

(Coos County) and in the Southwestern part of New Hampshire (Cheshire County).

It is called Big Leaf Lupine (Lupinus polyphyllus). It

has 11-17 palmately divided leaflets. The leaflets are much longer with a

pointed tip.

In New Hampshire, there are only a small number of Viburnums with lobed leaves:

In New Hampshire, there are only a small number of Viburnums with lobed leaves:

The Peterson Field Guide for Edible Plants says, ‘A European

ornamental occasionally escaped from cultivation,

V. opulus [Viburnum opulus var. opulus], is

almost a double for Highbush-cranberry, but with bitter fruit.”

For this reason, it is important to tell the two apart.

The Peterson Field Guide for Edible Plants says, ‘A European

ornamental occasionally escaped from cultivation,

V. opulus [Viburnum opulus var. opulus], is

almost a double for Highbush-cranberry, but with bitter fruit.”

For this reason, it is important to tell the two apart.

The leaves are edible (raw or cooked) when gathered in April or May before the flowering

stem appears. At this time, any slight bitterness can be reduced with cooking. Changes

to cooking water can reduce bitterness if the leaves are picked later in the Spring

after flowering. The rosette of leaves produced in the Fall tends to be mild and

can be collected into the very late Fall.

The leaves are edible (raw or cooked) when gathered in April or May before the flowering

stem appears. At this time, any slight bitterness can be reduced with cooking. Changes

to cooking water can reduce bitterness if the leaves are picked later in the Spring

after flowering. The rosette of leaves produced in the Fall tends to be mild and

can be collected into the very late Fall.